The Spanish local government system: A model designed for stability

Forty-five years after the first democratic local authorities took power, the available data shows that the local government system has been highly stable. Mayors are in office for around two terms (8 years) on average and changes of government during the legislative term are rare. Motions of no confidence are the only way to remove a mayor from office but there have only been between 150 and 200 motions per legislative period across 8131 municipalities.

Among the formal institutional elements that produce this stability are: a high legal threshold for representation on the council to avoid fragmentation, the strong mayor model as a form of government in which the mayor is the main political figure responsible for all executive functions, and a restrictive regulation of the motions of censure. On top of this legal architecture, is the fact that the national political parties – with a strong culture of party discipline - dominate local politics which reinforces stability. The rest of this piece discusses some of the key elements that make local governments in Spain highly stable.

More and less stable governments

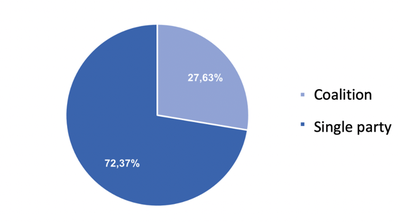

There is great stability in most local governments mainly because a single party has an absolute majority in the local assembly, the Council. Councillors from the majority party vote for their mayoral candidate in the mayoral election. Once elected, the mayor can form a one-colour executive with the council backing his/her proposals. Due to the intense implantation of national political parties at the local level, a large proportion of local governments in Spain are single-party governments supported by absolute majorities in the council and, therefore, very stable. This is the case for almost three-quarters of all local authorities in the 2019-2023 term.

Figure 1.- Single party and coalition governments in Spanish municipalities. 2019-2023

Source: own elaboration from Ministry of Interior data

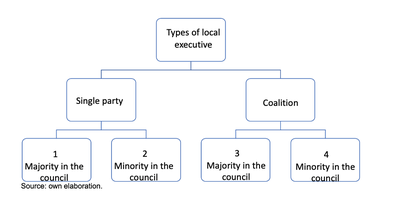

However, coalition governments are not negligible. Situations of greater plurality in government and in the local council may cause instability. This often happens when small political parties or individual or independent councillors switch their support from the mayor they supported in the mayoral election to other council leaders and parties, pursuing a change in the mayoral office through a motion of censure. Therefore, higher levels of instability may affect a single-party government with only a minority in the council and both types of coalition governments, with or without a majority (boxes 2, 3 and 4 in Figure 2 below). In these cases, local governments are more exposed to opposition strategies that seek to weaken them to the point of activating opportunities to take over through a motion of no confidence.

Figure 2.- Types of local government by political forces constellation

Indeed, the mayor can be recalled by the council. The legal system allows for motions of no confidence (legally referred to as motions of censure) against the mayor throughout his/her term of office. But the rules governing motions of no confidence are very demanding in their requirements: an absolute majority of councillors must support the motion and it must include a candidate for mayor in whom all councillors presenting the motion agree. Councillors that support a motion of censure tabled by another party lose part of their rights (right to join another political party, economic rights derived from the membership to the former party, etc.) and cannot participate in a new motion during the rest of the term. All these rules not only discourage instituting motions of no confidence but make the activation of such motions difficult. The data confirm the lack of incentives for motions of no confidence: for 45 years of local democratic governments there have only been about 200 motions of censure per term (out of 8.131 municipalities) and most of them took place in small size municipalities.

A high legal threshold and a residual clause for the election of the mayor

Among the main elements governing local elections that are presented below, the relatively high legal threshold for obtaining representation in the local assembly and the residual clause for the election of the mayor, reinforce the stability of local governments.

Elections are simultaneous in all municipalities. Each municipality, regardless of population size, is a single electoral district, and voters elect the council members. The number of councillors in the council varies with population size (ranging from 3 in the smallest municipalities to 57 in the largest city, Madrid). Elections follow an electoral proportional system using the D’Hondt method to allocate council seats.

Candidates are grouped in nationwide and regionwide party lists (in 95% of the cases) that are closed and blocked (without the possibility of altering the order of candidates on each list). National political parties dominate local politics, with 60% of the total councillors belonging to the two major national parties.

The legal threshold to get council representation is 5% of valid votes. This figure is higher than in national elections (3%) and is designed to avoid fragmentation and facilitate stability.

Twenty days after elections the mayor is elected in the first council session. Mayors are elected from among the council members heading party lists. The support of the absolute majority (+50%) of councillors’ votes is required to become a mayor. However, if a majority is not reached in the first vote, the councillor heading the electoral list with the most popular votes in the elections automatically becomes the mayor. This means that three weeks after local elections all municipalities in Spain (+8.000) have effective and legitimate governments.

The residual rule to elect the mayor (“if a majority is not reached in the first vote…..”) acts as an extraordinarily strong incentive for coalition governments in cases where no party gets an absolute majority in elections (around 25%). Parties with no majority in the council will try to form alliances (ideologically acceptable) to vote for a mayor and share the government portfolios later in a multiparty cabinet. Parties with the most (but insufficient) votes will also try to attract members of other party/s to coalition governments, offering them portfolios in the local cabinet in exchange for support to their candidate mayor.

The strong mayor form of local government

Horizontal power relations among the three structures of local government (mayor, local assembly and top public administrator) follow the strong mayor form. This implies that the form of local government is based on an elected executive as the central figure of the government. The elected mayor controls the majority of the council and is, in terms of the law and practice, in full charge of all executive functions. The top administrator (the CEO) serves at the mayor’s will. The mayor can hire political appointees to help in any function.

Given that the structural features of municipal government in any country reflect a balance or compromise between three organising principles (citizens’ representation, political leadership and professionalism), the strong mayor form and, therefore, the Spanish system of local government is an example of an institutional design that emphasizes strong political leadership over citizens’ representation (as in the collective form of government) and professionalism (as in the council-manager form).

This form of government gives the mayor extraordinary powers. We could say that once elected, mayors can effectively steer government action even, in extreme cases, without the support of the council, as long as a motion of censure is not presented and succeeds. Mayors can make most decisions on the day-to-day functioning of the municipality, including those related to procurement processes. Only the most important decisions such as the approval of new by-laws or the annual budget need to be passed by the local assembly. But many mayors navigate these circumstances daily. In search of more stability, the law was reformed in 1999 to enable mayors without clear governing majorities on their councils to approve annual budgets by means of the rejection of a special type of confidence motion. Under this method, the mayor stands for a no confidence vote and if it is rejected by the council (i.e., if it does not gain an absolute majority), the annual budget is approved.

Conclusion

One of the aims of Spanish lawmakers during the transition to democracy in the late 1970s was to create stable political institutions. The upheavals of the 1930s, which ended in a fratricidal civil war, and the subsequent 40 years of authoritarian rule had left their mark. Forty-five years later, the stock is positive. The local electoral rules (legal threshold, rules for electing the mayor) and the system of local government (strong mayor form), with the help of a culture of strong party discipline, have managed to achieve this.

By Carmen Navarro, University Autonoma of Madrid

Carmen Navarro is a visiting Professor from the University Autonoma of Madrid. This article was produced while she was on secondment at the Dullah Omar Insitute as part of the 'Local Government and the Changing Urban-Rural Interplay' project, which received funding from the European Union‘s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 823961.