One step forward, two steps back: 2021 local government elections resulted in lower women’s representation than the last few elections

What do the numbers say nationally from 1995-2021?

While steady progress has been made since 1995 (with a slight dip of 2% in 2011), the 2021 figures show that total women’s representation in local councils has fallen by 4.1% since the last election. Table 1 below shows that Women’s representation in PR seats, which we once commended, has fallen significantly, from 48% in 2016, to 24.2% in 2021, while women’s representation in ward seats has fallen from 33 percent in 2016 to 12.7% in 2021.

The Covid-19 pandemic and related mobility and gathering restrictions may have contributed to the reduced participation of women as candidates for local government elections in 2021. Women as primary care givers carried an increased burden of care during the pandemic due to stay-at-home orders, working from home, home-schooling, and restrictions on group gatherings and political gatherings including door-to-door campaigns, which may have reduced the ability of women candidates to canvass support. Additionally, in the 2021 elections at least 14 candidates were murdered, which may emphasise that local government elections are dominated by egos, crude politics, and, toxic masculinity, and the attraction of ‘paid employment'. This makes it difficult for men, but more so women, to compete in such an environment.

In 2021 we also saw an increase in the number of small political parties, which indicates an active participation in democracy and creates more opportunities for wider representation of community interests. However, in the absence of national legislation compelling parties to have gender-balanced party lists, and enforcing this, it remains at the discretion of political parties, whether to have women represented or not. If parties with gender-balancing policies, such as the ANC, lose support, it leaves parties without gender-balancing policies. This could help explain why the 2021 local government elections have resulted in such a low percentage of women elected on PR seats.

Table 1: Women's representation in ward and PR seats from 1995-2021

| Year | Women (ward seats) | Women (PRS seats) | Women (overall) |

| 1995 | 11 | 28 | 19 |

| 2000 | 17 | 38 | 29 |

| 2006 | 37 | 42 | 40 |

| 2011 | 33 | 43 | 38 |

| 2016 | 33 | 48 | 41 |

| 2021 | 12.7 | 24.2 | 36.9 |

Source: Date from IEC

What do the numbers say at a provincial level?

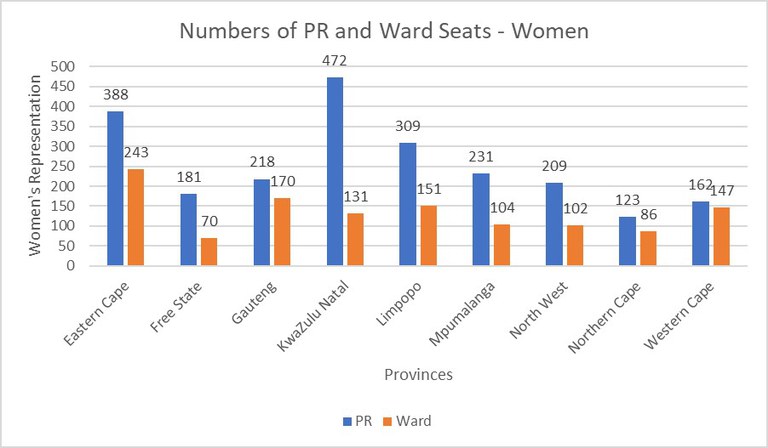

Disaggregated by province, the statistics with regard to women’s representation in local government show that once again, PR seats have resulted in a higher number of women being elected into council through PR seats, in contrast to ward seats.

As can be seen from Figure 1 below, KwaZulu Natal is leading with 472 women (25%) in PR seats, but it also has the lowest number of women elected to ward seats 131 (7%). This could be reflective of KwaZulu Natal having strong support for the ANC, as the ANC follows the zebra list system for its PR list, and combined with the fact that KwaZulu Natal has the largest number of council seats, which impacts on the PR seats available. The downside is that the significant difference between the PR seats 472 and the ward seats 131 could be a symptom of deeper societal prejudice against women and a tendency towards patriarchy.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is the Western Cape, a DA stronghold, where the women elected to PR seats – 162 (19%), is very close to the number of women elected into ward seats – 147 (17%). The DA’s party policy advocates for women to stand on merit as opposed to using a zebra list.

Figure 1. Provincial Stats: PR vs Ward seats

Source: Data from IEC

What do the numbers say at metropolitan level?

Table 2 below illustrates the distribution of PR and ward seats won by women in the 8 metros.

PR seats- The situation in metros is disturbing, with the highest female representation in terms of PR seats being 23% in Mangaung, and the lowest being Tshwane at 14%. In terms of party differentiation, in Mangaung, which has the highest number of PR seats for women, the ANC won 50.63% of PR seats), while the DA won 25.73% of PR seats, and the EFF won 11,31% of seats.

Ward seats- Buffalo City has the highest number of women elected into ward seats, at 21% and the lowest is in Nelson Mandela Bay at 8%. In Nelson Mandela Bay, which has the lowest number of women elected into ward seats, the DA won 39.92% of seats, ANC 39.43% and EFF 6.4%. These numbers illustrate that gender-balancing policies make an enormous difference when there is no law enforcing the obligation to ensure gender balance in party lists.

Table 2: Elected Candidates in PR and ward seats by gender and metro as a percentage of total votes in that metro (rounded up)%

| Metro | PR Female | Ward Female | PR Male | Ward Male |

| Buffalo City | 21 | 21 | 29 | 29 |

| Nelson Mandela Bay | 20 | 8 | 30 | 42 |

| Mangaung | 23 | 16 | 27 | 35 |

| Ekurhuleni | 19 | 15 | 31 | 35 |

| City of Johannesburg | 20 | 17 | 30 | 33 |

| City of Tshwane | 14 | 15 | 36 | 35 |

| eThekwini | 23 | 10 | 27 | 40 |

| City of Cape Town | 18 | 18 | 32 | 32 |

Source: Data from IEC

What does this mean in practice?

Electing women into local government can advance women’s issues through legislative, planning and budgetary processes. For example, Rwanda has the highest level of women's representation in parliament in the world at 48.75 per cent, and according to Devlin and Elgie, ‘women's issues are now raised more easily and more often than before’.

The fact that not even half of our councillors are women, means that municipal councils- the bodies responsible for adopting by-laws, integrated development plans, spatial planning, zoning, and municipal budgets- may overlook serious issues that are of concern to women, simply because women are not present in the room. While men may be aware of these issues, not all men will raise them in council, and not all men will be able to make the connection between what seems to be gender neutral and the disproportional impact of municipal regulations and council decisions on women because it is not their lived reality. Many of our municipalities’ responsibilities are central to women’s daily lives. For example, municipal water, electricity reticulation, child care etc., which tend to fall on women due to the systemic gendering of the roles of cooking, cleaning and caring (unpaid care work and reproductive work). While acknowledging that there are households were men undertake the same roles, it is important to note as reported by UN Women that globally women still carry a disproportionate care and time burden. Women also experience public services differently from men, for example, women’s experience of water service delivery is different from that of men. Women need water not only for daily hygiene, but also additional water for menstrual hygiene, and post-natal hygiene for example. This makes local government functions especially important to women, and more so in informal and rural settings. Further, as noted in an earlier article statistics of gender-based violence and femicide (GBV(F)) are staggering and, as a result, women also have to consider issues of safety and security in all aspects of life. Spatial planning that considers the various issues such as infrastructure, integrated transport systems, distance to places of work, and street lighting inter alia, that affect women will have an impact on women’s quality of life and realisation of their human rights.

However, it is not enough to elect women councillors, but they also need to be empowered to articulate women’s issues and influence policy and legal reform. Further, the duty of accountability falls on both men and women councillors equally. For example, while increased women's representation has contributed to increased opportunities for raising women’s issues in Rwanda as noted above, it has not translated to changes in policy outputs. Not all elected women will be able to raise women’s issues in council, for many reasons, such as not being able to articulate them, seeing issues as being part of private life and not as issues that should (or can) be addressed by their local government, not wanting to appear weak among peers in this male-dominated sector, among other things. Moreover, not all women’s issues raised in council will be adopted by the council for implementation because the numbers are still heavily skewed in favour of men, and also because not all women perceive women’s issues in the same light (women are not a homogenous group). As a result, it is important to train all councillors, male and female on the gendered dynamics of governance processes and decisions. It is important to draw from the knowledge and experience of the few women who have been elected as councillors and build on that to ensure that having women political representatives actually translates to having a stronger voice for women issues. The point is not to negate men’s issues, but to bring a gendered lens to municipal governance because decision-making in councils is not gender neutral.

Conclusion

To conclude, after the 2021 local government elections, we now have even fewer women representatives, compared to the last three local elections. This shows that South Africa has taken one step forward, and two steps backwards in ensuring gender equality on municipal councils. We continue to rely on political parties’ gender policies to instruct their party lists, which puts the gender-equality agenda at their mercy. Until the IEC is empowered to monitor party lists and enforce gender balance on these lists, we may be fighting a losing battle.

Moreover, it is now, more than ever, important for women to take part in local government more actively, not only as councillors but also, as citizens. Women should actively engage their councillors and hold them to account for the promises made to women in their manifestos.

By Michelle R Maziwisa, Postdoctoral Researcher